by Shen Shi'an, The Buddhist Channel, March 6, 2011

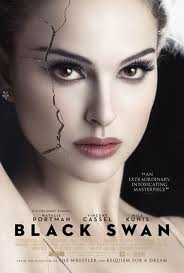

Singapore -- ‘Black Swan’ tells the story of extreme clash of conflict in body and mind. A ballerina feels compelled by her idealism and expectations of others to play both the pure and restrained white swan and the malevolent and seductive black swan in a revised version of Swan Lake. In order to embody her roles perfectly, she swings to and from between goodness and evil. Can she play a perfect white and black swan at almost the same time? A whole list of other paradoxical extremes are explored too…

Perfection in dance is not just about hard discipline, but about letting go for natural ease too – even as the black swan. Where does creativity and control find a balancing point, or are the meant to be balanced at all? How much effortful grit is needed for effortless grace? There is control in true letting go and letting go in true control. Can stiff control and wanton passion be moderated? Is a good dancer ultimately repeatedly and robotically precise in the same old ways? If so, how is it original, raw and creative art? Even the revamped take on Swan Lake had to be covered repeatedly in rehearsals, rebirthing through heaven and hell.

Too schizophrenically improbable, perhaps it is not realistic for one person to rapidly and alternatively play both swans. Overly immersed in the roles and challenged by not being used to playing the doppelgänger ‘evil twin’, the ballerina develops psychosis, as she starts to internalise the black swan, who expresses her metamorphosis inside out by hallucinating the sprouting black feathers out of her body. The more she externalises the black swan, the more she internalises the black swan. In a vicious cyclic manner, she become the performance as the performance becomes her. The darker her consciousness became, the more she imagined another ballerina who plays the black swan too to be truly black-hearted too. This is the externalisation of inner demons.

In an artistically sickening way, the more indulgent she is, the more expressive she is. The more punishing her practice became, the more ‘rewarding’ it twistedly became. The creative arts for bettering the psyche can be damning and destructive too when taken to its extremes, as with any other thing. As with other controversial arts and even films, perhaps the Buddha’s teaching of the Middle Path should be heeded – to recognise that nothing should be taken to any extreme. Is this movie an extreme one then, of how the arts can become dark? Yes, in a way, but yet paradoxically extremely good as a cautionary tale!

Perhaps the performance arts for serious actors who become the acting is not karmically neutral after all? If one always plays villainous roles as if they are real, does one create some negative karma? Must drama always be so dramatic to be real, or is real life a subtler and grayer mix of light and darkness? Paralleling real life, she dies in the last scene of as the white swan, with her innocence killed by the black swan within. Seemingly a tragically bleak and beautiful ending, as she exclaims her last dance to be perfect. But is art worth dying for, especially that based on illusion? As her instructor advised earlier, ‘The only person standing in your way [of performing well] is you. It’s time to let her go. Lose yourself.’ But she had lost too much – she had lost sight of her perfect Buddha-nature too, overwhelmed by her inner Mara.